Stop Romanticizing 19th Century Europe!

Europe in the age of Metternich & Bismarck was not peaceful

There’s a tendency among many realists to portray 19th century Europe, more specifically the century between the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 to the start of the first world war in 1914, as a kind of golden age of peace and prosperity in European history. This was understandable for the generation who lived through or came of age in the immediate aftermath of, the two world wars. Compared to the sheer barbarism of the world wars (1914-18, 39-45) and the chaos of the interwar years, the 19th century was atleast comparatively more stable (atleast for certain regions of the European continent).

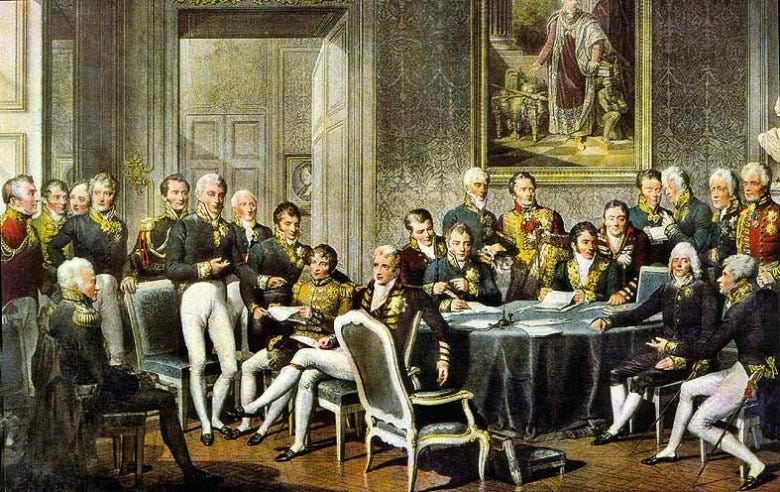

In this context, theorists of international relations (particularly those of the dominant ‘realist’ school) were more than eager to credit this alleged golden age to an informal system created during the Congress of Vienna known as the “Concert of Europe”. According to this view France’s efforts to dominate the continent had led to a nearly unbroken quarter century (1792-1815) of fighting across the whole of continental Europe, with left millions dead, the victorious great powers of Europe brokered a restoration of the status quo ante at the Congress of Vienna. The order these great powers established was based around a ‘balance of power’, in which no single power would be allowed by any of the others to dominate the continent (as France had attempted). An appealing framework to those wracked by two recent attempts by Germany to dominate Europe.

The reality is a lot darker and more complicated however. To understand this, consider the map of Europe in the immediate aftermath of the Congress of Vienna.

For starters, to placate expansionist states like Austria, Russia and Prussia, the Great Powers agreed to allow both allow forcible annexations of territory and spheres of influence over dominated client states. The interests of smaller states (e.g Poland) to be free and avoid annexation were dismissed by statesman of the day as a nuisance, something that aroused the public opinion of ordinary people in Britain, thereby making the task of reaching a concordance among the great powers (the only ones who mattered in the minds of the diplomats at the Congress of Vienna) more difficult. The diplomats solved this “problem” of international solidarity between Brits and Poles by granting Poland a fig-leaf of pretend sovereignty under a nominally democratic constitution (while in actuality conceding it to absolutist domination by the Russian Tsar). Italy meanwhile, was kept as a balkanized patchwork of client states under the domination of the ultra-reactionary Austrian Empire.

This temptation is atleast familiar and not fully alien to our own age, even if it violates the norms on which the modern international system is built, in which states are legally considered sovereign and self-determining equals. John Mearsheimer for example has suggested conceding Ukraine to a Russian sphere of influence and routinely castigates western countries for trying to draw (allow would be a better term) Ukraine into the Euro-Atlantic community of states. Realists are used to thinking of the world in a hierarchical way based on the degree of power a state has in the international system and role it plays.

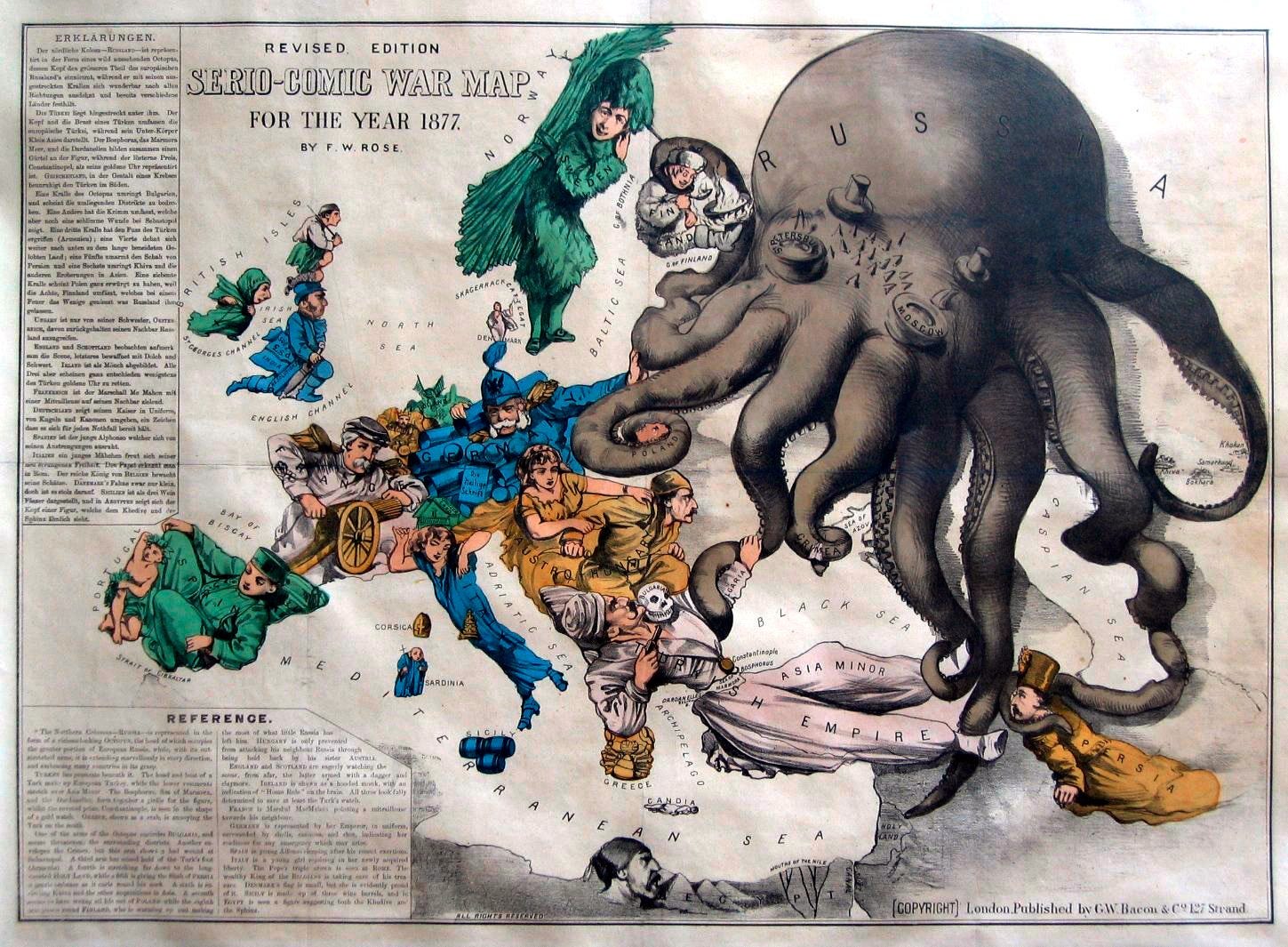

However, beyond whatever moral qualms might have about consigning entire nations to oppressive domination by foreign empires, the system didn’t actually work to keep the peace. France sought to expand its power and influence at the expense of both Austria and Russia, meanwhile Russia had ambitions of expanding its influence at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, France and Britain, at the same time that Prussia had ambitions of expanding its influence at the expense of Denmark, Austria and France, while Sardinia had ambitions of national unification that directly challenged Austria’s sphere of influence, even as Austria sought to expand into Ottoman Empire. These rivalries in turn led the great powers to come to blow with the Greek War of Independence (1821-1833), the First Schleswig War (1848-1851), the Crimean War (1853-1856), the Franco-Austrian War (1859), the Dano-Prussian War (1864) the Austro-Prussian War (1866), the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), the Russo-Turkish war (1877-1878), the Austro-Hungarian invasion of the Ottoman Empire (1878). And those are just the wars involving Great powers, I haven’t even mentioned yet the numerous revolutions and revolts that came from below (e.g the revolutionary waves of 1820, 1830, 1848, 1875).

If that all sounds awfully confusing and convoluted, don’t worry, the statesman of the day could hardly understand it all either. Lord Palmerston, who twice served as Prime Minister and dominated British foreign policy from 1830 to 1865, once remarked about the Schleswig-Holstein war between Denmark and Prussia "Only three people have ever really understood the Schleswig-Holstein business – the Prince Consort, who is dead – a German professor, who has gone mad – and I, who have forgotten all about it." And that was just one of the many mid-century wars which brought European armies to blow over this period. At a high-level though, nationalism, democratic-egalitarian aspirations, and great power rivalry was constantly destabilizing the reactionary order of repressive monarchies, multi-ethnic empires and balkanized nations, that Metternich had attempted to restore during the Congress of Vienna.

It wasn’t simply that the Great Powers had rivalries, Great Power rivalry remain a feature of the 21st century (as anybody familiar with Sino-American relations will attest to). It’s that these rivalries would frequently and casually erupt into major wars between the Great Powers. I’m not talking about minor border skirmishes like that result in a handful of deaths in the Himalayas without anybody noticing, I’m talking about whole armies being mobilized resulting in the deaths of tens to hundreds of thousands of people and occasionally even destruction of a European capital like Paris. I want to take a moment to emphasize how bizarre this all would be in a modern context. Under what circumstances is it even possible to imagine, France and Germany fighting a full-scale war against each other, let alone Germany going to war with Denmark or Italy and France teaming up to wage war on Austria? In the mid-19th century these wars not only happened but were quite normal and treated almost as matter of course in international relations. Even the potential wars we can more plausibly imagine taking place (e.g NATO against Russia in Ukraine, the United States against China over Taiwan) are considered so extraordinary as to be more or less synonymous with the end of the world as we know it. The 19th century Great Powers by contrasted treated war as, in the immortal words of then contemporary Prussian political theorist Carl von Clausewitz, “the continuation of politics with other means”, which led to the casual settling of issues by blood rather than by diplomacy or international arbitration.

Just as there were frequent wars from above by the great powers, so too there were frequent revolts from below. Liberals and socialists likewise didn’t just sit down and accept a transparently unfair, elitist, reactionary, and anti-democratic political order. They contested it, leading to wave after wave of violent revolution destabilizing governments. In 1820, in 1830, in 1848, in the 1870s. Nationalists of this era no more accepted that their nations would remain balkanized or under the boot of a foreign empire, than Ukrainians today accept Russian occupation. Italians resented being fragmented and dominated by the Austrian Empire, Germans resented being fragmented under conservative monarchies that denied them popular sovereignty, the various peoples of the Balkans resented the oppression they faced under the Ottoman Empire, the Poles resented living under the Tsarist boot. When nationalist and democratic uprisings were repressed, they simply reoccurred decades down the line due to the old grievances remaining unsettled.

Indeed, what strikes one reading about this period is the overwhelming sense of futility with which the great powers attempted to resist the historical forces at work. Britain and France for example, would repeatedly intervene to prevent the Ottoman Empire, at this point in terminal decline as the ‘sick man of Europe’, from collapsing into smaller Balkan nation-states, their efforts ultimately serving only to defer the collapse of the moribund Ottoman despotism. The Austrians brutally repressed the Italians and Germans 1848 seeking national unification and liberal democracy, only to be defeated in the second and third Italian wars of independence in 1859 and 1866 respectively. The Tsar repressed the Polish aspirations for self-government, only for them to revolt repeatedly in 1830-31, 1863-64,1905-07, before ultimately achieving independence in the Polish-Soviet war of 1918-21.

There was something of a reprieve that emerged later in the century, as the focus of the Great Powers shifted to competing in other theatres through the expansion of overseas colonial empires (the so-called “Scramble for Africa”) it would barely last another three decades before the cataclysm of the First World War.

The first world war wasn’t an aberration or a betrayal of the world of Metternich and Bismark helped create, it was its culmination. The Europe one sees today today, a Europe in which France can no more imagine going to war with Germany than can California against Texas, owes less to the overromanticized world of Bismark and Metternich, than it does to the liberal order founded in explicit rejection of this past history.

This isn’t simply a story of American hegemony as its often portrayed. The hegemony of the Russia over its satellite states in Eastern and Central Europe during the Cold War, but rather exactly the kind of repeated uprisings and repressive invasions that characterized the century before it (e.g anti-Soviet partisan insurgencies of the 40s, 50s & 60s, the 1953 East German uprising, 1956 Hungarian Revolution, 1968 Prague Spring, 1980 Solidarity revolution, the 1989 Revolutions). Rather, it was a liberal peace.

Since 1945, liberal democracy and intergovernmental organizations have progressively expanded to the point where, even now, war has become an aberration rather than a normal way of doing business across the vast majority of Europe. The continent has been largely united, not by a conquering empire imposing its hegemony, but by the voluntary joining together of free and democratic sovereign states into a confederation devoted to trade, cooperation, and collective defense. In 70 years, no member of NATO, the EU or any of its predecessor organizations, has fought a war against another member state. Domestic civil wars and secessionist insurgencies have become both rare and settled in ways that resulted in sustained peace and accommodated desires for self-government rather than recurrent outbreaks of violence (e.g the Greek civil war, the Basque conflict, Northern Irish troubles). Germany, for centuries the epitome of a reactionary and militarist state (including its Prussian predecessor), became a pacifist social market economy that settled its century of enmity with France. Authoritarian regimes, from the fascist states of the Iberian peninsula, to the communist regimes of the former Warsaw Pact have become transformed.

I don’t wish to overstate my case. Turkey remains both authoritarian, embroiled in a long-term confrontation with Greece (albiet one that hasn’t even come close to war in almost 50 years), and engaged in its own dirty wars in the Middle East. Russia remains a belligerent and reactionary power beyond the periphery of this liberal order which to this day continues trying to undermine the values and strength of the liberal democratic world. Illiberal authoritarian politics continue to have sway in a number of European capitals, from Budapest to Warsaw. The proclamations of an end to history by Fukuyama were indeed premature. But the long view of history should make us both grateful to be living in the 21st century and not the 19th, and it should make us confident in the enduring superiority of the liberal democratic project over the dirty deal-making of Metternich and Bismark.